Ottoman Sephardic Genealogy: An Introduction

Page 1.

by Dr. David Sheby

(Images annotated by David Sheby and Shelomo Alfassa)

Scope

This Introduction provides tools, techniques, and resources for researching genealogy of Ottoman Sephardim. In this Introduction the following definitions apply:

Sephardim: Ladino speaking Jews whose ancestors lived on the Iberian peninsula prior to the 1492 Expulsion. It is not a term for non-Ashkenazi Jews. (Notes: [1] A variant of Ladino is "haketia" that is spoken by Sephardim of Moroccan and other North African communities. [2] There are differences among scholars on the appropriate name for the language spoken by Sephardim. Professor Isaac Jerusalmi (USA) prefers "Ladino", Professor Haim-Vidal Sephiha (France) prefers Judeo-Espagnol (or Judeo-Spanish), and Professor David Bunis (Israel) prefers "Judezmo".)

Sephardic: having a quality associated with Sephardim.

Sephardica: objects/themes of a Sephardic nature. Usually referring to memorabilia or collectibles.

Sephardic genealogist: a generic term for a person engaged, or interested, in the process of reconstructing one or more Sephardic families' lineages (i.e., identifying the places of, dates of, and participants in, the chain of child-producing cohabitations comprising the lineage) extracted from contemporaneous records and/or artifacts such as inscriptions, dedications, tombstones, dairies, community records, commercial transactions, correspondence, government documents, etc.

Version 1.0 of this Introduction covers resources, tools, and techniques for Sephardim living in those regions of the Ottoman Empire comprising the Balkans, western Turkey ("Turkey-in-Europe", and the western coast of Anatolia) and the Aegean Islands.

This is a work in progress. The data is this Introduction is accurate through July 2000.

Note: Accepted conventions of transliterating Arabic and Turkish words are not followed in this Introduction.

1.0 Getting Started

The material of interest to a Sephardic genealogist is spread over a great variety of sources, much of which was originally published without intention of being used for genealogical research. Such material resides in the vast literature of (non-genealogical) Jewish studies, Ottoman economic history, and Ottoman philately (i.e., stamp collecting).

For example, studies in Ottoman economic history often mention the interaction of Jewish merchants with European counterparts from the 17th through early 20th centuries. How were the identities and numbers of the Jewish merchants in such studies established? The answer is in the archives of diplomatic and commercial correspondence, identifying these merchants by name, that were accessed by the original research. But in the subsequently published studies in academic journals specific names were not required for the purposes of the papers and were omitted. One task of a Sephardic genealogist is to revisit many of these studies to identify relevant archives. Such a strategy is discussed, with examples, in this Introduction.

The identification of useful material for the Sephardic genealogist is a continuing and evolving process. Consequently this Introduction cannot claim to present all relevant tools, techniques, and resources of use to the Sephardic genealogist as the useful source list has not been finalized. Nonetheless, this Introduction attempts to:

(1) identify a set of tools for working with some of the important written material that the Sephardic genealogist is likely to encounter;

(2) identify available material of high Sephardic-genealogical content useful for obtaining information about specific families or communities; and

(3) provide, by example, methodologies for identifying new sources containing Sephardic genealogical information.

1.1 Essential Reading (Core Material)

Sephardic genealogical material (such as articles and/or book reviews of specific family or community histories) is often embedded in publications dealing with Sephardic culture in general. A prime example is found in the catalogue (for the Israel Museum's exhibition on Ottoman Jewry at the Jewish Museum of New York): Juhasz, Esther (Editor), Sephardi Jews in the Ottoman Empire: Aspects of Material Culture [ISBN 965-278-0650, 280 pp., 391 illustrations 111 in color, text: English] [referred to as (Juhasz (1990)]. This volume provides broad and indepth coverage of the material objects used in the life cycle events of the Ottoman Sephardim. Many of the illustrated items, understandably, are not described for their utility to genealogical research, but for their artistic or stylized characteristics.

The personal information contained in dedicated ritual items is often not indexed separately undocumented for interested genealogists. Figure 1.0 (taken from Juhasz (1990), p 79, "inner and outer Torah ark curtain" from the Etz Hayyim synagogue in Izmir) reveals, for example, some information about the Politi family: a) that Raphael Politi was a member of that congregation in 1921; b) his father was Nissim Politi; and c) his paternal grandmother was Rosa Politi (maiden name not provided). Hence an index of the Juhasz book, indexing its genealogical content would be a useful exercise for a Sephardic genealogist to undertake. Examples of the genealogical data extractable from the Juhasz book are discussed in this Introduction.

Figure 1.0: Example of genealogical information (for the Politi family) extracted from a synagogue tapestry (in Izmir). Source: Juhasz, Esther (Ed.), Sephardi Jews in the Ottoman Empire, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1990, Figure 17, page 79.

A of core set material providing important guidance for the Sephardic genealogist exists among the following publications and Internet web sites:

#1 ETSI (a Paris-based, bilingual French-English periodical) is devoted exclusively to Sephardic genealogy and is published by the Sephardi Genealogical and Historical Society (SGHS). It was founded by Dr. Philip Abensur, and his professional genealogist wife, Laurence Abensur-Hazan. ETSI's worldwide base of authors publish articles identifying a broad spectrum of archival material of importance to the Sephardic genealogist. ETSI's web site (containing subscription information) is located at the follwing address:

http://www.geocities.com/EnchantedForest/1321

A useful feature of ETSI is the listing, on the back cover, of all Sephardic family names, and places of origin, cited in the articles contained in each issue. ETSI publishes specialized bibliographies of material written about a particularly community. ETSI is undertaking a variety of important archiving tasks, i.e.,:

(1) a listing of all known Ladino-language newspapers and the libraries/archives which have copies of those publications;

(2) identification of all known Sephardic ketubot and the universities/museusm/archives in which they are contained; and

(3) listing of its membership's family/city interests.

#2 An important guide for Sephardic genealogists is the article:

Abensur-Hazan, Laurence: "The Current State of Sephardic Jewish Genealogy", Avotaynu, vol. XV, Number 1, Spring 1999, p. 37-38

#3 It is important to emphasize that a genealogist should never assume that what he/she is reading is known to other genealogists. Notes should be taken on family names, archive sources, place names, and types of data available (maps, census results) that can be shared with others. Internet sites are rapidly taking on the much need role of centralized repositories where individual researchers can deposit their research notes as well as individual memorabilia (such as photographs) to rapidly build specialized collections and databases available to a worldwide readership. There are several web sites which pioneered Sephardic genealogical, historical, and cultural content on the Internet. These sites are labors of love, and have become important repositories of information gathered by the owners/authors and a wide network of corresponding Sephardic genealogists.

i. Jeff Malka's "Sources for Sephardic Genealogy" at http://www.orthohelp.com/geneal/sources2.HTM. (Also see: Malka, J: "Using the Internet as a tool for Sephardic Genealogy", ETSI, No. 2 (Autumn, 1998), pp. 10-12).

ii. Harry Stein's "A Research Tool for Sephardic Genealogy / Jewish Genealogy" at http://www.sephardim.com

Valuable genealogical data is available in the family trees / newsletters that are available through the Internet. Because of the personal nature of their contents they are not itemized, or described, in this Introduction. Additional reading material is described below in this Introduction.

1.2 Ottoman Birth Certificates

Figure 1.1 shows an Ottoman birth certificate with superimposed English translations on important sections. [Note: This certificate was generously made available to this Introduction by its owner, Mr. Nick Demetrion. The birth certificate is of Mr. Demetrion's mother Penelope (née Vassiliadis), whose family were members of the Millet-i Rum (i.e. Greek community)]. The text is printed in Arabic lettering. The Ottoman Turks, like the Persians, adapted the Arabic alphabet for their non-Semitic language. To capture certain sounds (like "p") absent in Arabic, the Ottomans borrowed some of the Persian's letter-innovations for the Arabic alphabet. The Ottoman Turkish language written in Arabic script is referred to as osmanlica ("Osmanli" means Ottoman).

A birth certificate for a citizen of the "Musevi" (Jewish) millet, translated by a different translator, is shown at: http://www.sephardicstudies.org/otto_bc1_front_marked.jpg)

A Sephardic genealogist can learn to read Ottoman type-set text (such as the printed form of Figure 1.1) by studying "how to" books on Arabic script. It is the handwritten entries that are very difficult to read. Arabic script can be written in a variety of styles. For handwriting, the Ottoman Turks used a style called "riq'a" or ruq'ah. Arabic script is different from most alphabets in that some of the letters can take on as many as 4 different forms based on whether the letter appears at the front (initial) of a word, the middle or end of a word, or in an isolated position. These variations in handwritten script is complicated by individual's short cuts to abbreviate certain vowel signs and individualize letter combinations known as ligatures. The interested Sephardic genealogist is referred to the book Mitchell, T. F.: Writing Arabic: A Practical Introduction to the Ruq'ah Script, Oxford University Press, 1990, ISBN 0-19-815150-0 which contains particulary valuable charts (pages 138-148) showing the appearance of letter-triplets. Thirty-seven (37) pages of osmanlica with the equivalent word transliterations into Latin characters can be found in: Jerusalmi, Isaac: From Ottoman Turkish to Ladino, Ladino Books, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1990, ISBN: 1-878-191-01-2 and is very good for practicing one's reading (not comprehension) of legible osmanlica.

Note: the reader may notice a number of references in this Introduction to Ottoman philatelic (stamp collecting) publications/sources. Ottoman philatelists share certain common interests with the Sephardic genealogist. Ottoman philatelists need to: (1) decipher Ottoman dates (for postal markings, hence are keenly interested in the Ottoman calendar system); (2) know where certain towns were located (to identify post offices and alternate town/city names during and after Ottoman administration), and (3) to have knowledge of Ottoman writing styles (to decipher notations on postal material and to read postal cancellations) and documents (which may have certain types of "revenue" stamps affixed).

The ornate design on the top of the birth certificate is a tughra, which is a highly stylized and individualized signature (or monogram) of the reigning Ottoman Sultan.

The tughras for the Sultans whose combined reigns covered the period 1876-1922 are shown in Figure 1.2, 1.4, and 1.5

For a breakdown on the line structure comprising the inscriptions embedded into the tughra of Sultan Abdulaziz (reign: 1861-1876: formal name: Abd ul-Aziz han bin Mahmud el-muzaffer daima (from: Birken, Andreas: "The Tughra of Sultan Abdulazia (1861-1876)" Journal Oriental Philatelic Association of London (OPAL), volume 174) see: http://home.t-online.de/home/A.Birken/tughra.htm.

Figure 1.2 Tughra of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (1876-1909)

Right: Figure 1.3 Example of the Tughra of Sultan Sultan Mehmed V on an Ottoman Turkish coin of 1911 CE.

Figure 1.4 Tughra of Sultan Mehmed V (1909-1918)

Figure 1.5 Tughra of Sultan Mehmed VI (1918-1922)Tughras can be found on coins (Figure 1.3), stamps (Figure 1.8), and craftwork (such as silver coffee pots or serving dishes). They are useful for dating an item to within the reign of a specific Sultan. The tughras for three Sultans of the early 20th century are shown in Figure 1.2, 1.4 and 1.5. If the tughra consists of a smaller symbol to the right of a larger design (as in the tughras of Sultans Abdul Hamid II, and Mehmed V), then the smaller design is an "adjective" describing a virtue of the Sultan. The larger motif contains the Sultan's name and is used for dating. (Note: for a translation of Sultan Abdul Hamid II's tughra see: http://home1.gte.net/eskandar/hamidtughra.html). The tughra in Figure 1.2 is that of Abdul Hamid II who reigned from 1876 to 1909. (NOTE: All the Ottoman Sultans' tughras are illustrated and analyzed in: Umur, Suha: Osmanli padisah tugralari, Cem Yayinevi, Istanbul, 1980, 327 p. : ill. (some col.), facsims. ; 29 cm, Library of Congress Classification: NK 3636.5 Z6 T848 1980.) There are two ways to date this birth certificate.

a) By direct translation, which will yield precise birth date and place of birth information, which requires an ability to read handwritten Ottoman Turkish (Ottoman documents from the 19th and 20th centuries are usually printed, and filled in with handwritten text; or

b) By using the tughra for approximate dating together with any revenue stamp at the bottom of the document: a stamp's issue date and the tughra provide an earliest, but not precise, date for the document.

Figure 1.6 Demonstrates areas of the Tughra which are unique and aid in identification. Notice how A1. has a larger circle then A2. Also observe that the area of B2. has horizontal lines, compared to a similar area which has a circle near B3.1.2.2 Numerals and Years

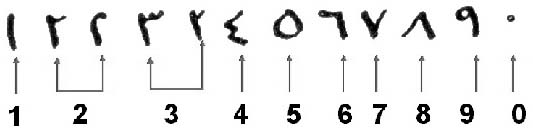

Figure 1.7 Arabic numerals 1-9 and 0 showing variations in the numerals "2" and "3" encountered in handwritten text. Unlike most tables of Arabic numerals, shows the two distinct variations of the numerals "2" and "3" that are often encountered in handwritten texts. Arabic words are written right to left (and sentence read right to left), Arabic numbers (and years, and days of month) are read left to right. The "5" is circular, and the "0" is a dot-shaped. Adapted and reprinted (with permission) from: Rose, Richard B: "Reading Ottoman Dates" (Oriental Fiscal Calendar 1867-1923). March 1988, OPAL (Oriental Philatelic Association of London) ISSN 0267-8071.

Figure 1.8 An example of an Islamic style date (1327) taken off an actual Ottoman stamp.

1.2.3 Ottoman CalendarThe Republic of Turkey (modern Turkey) adapted the Gregorian calendar in 1926. Before that the major change in the Ottoman calendar occurred in 1789. At that time (1789) a "fiscal" or "civil" calendar was introduced that ran simultaneously with the Islamic (or religious) calendar. From 1789-1926 this fiscal calendar was tied to the "JULIAN" Year, not the Gregorian calendar, because of the many Greeks/Slavs within the Empire who used that calendar. The names of the months for the fiscal calendar are different from the names of the months for the Islamic calendar as listed below. The fiscal calendar was eventually used by the Ottoman post office, but not on all official documents. (There are cases where the post office would switch the use of dates).

Hopefully, if readers of this page submit copies of their family birth certificate, this page will be able to make a more substantial statement about the dating used on the birth certificates. The Islamic calendar is 4 digit calendar, typically starting with the numeral "1". Sometimes this numeral is dropped for convenience and the date is represented as a 3 digit numeral. This is usually in Arabic lettering. An approximate means to get from the 4 digit Islamic calendar year to the Gregorian year is to add "584", i.e., 4 digit Islamic year + 584 = 4 digit Gregorian year. Table 1.1 lists the Islamic/religious months in both their Arabic and Turkish names. Table 1.2 lists the Turkish names of the months in the new calendar system also known as the "maliya" calendar.

|

Table

1.1 The Islamic (Religious) Calendar used in the Ottoman Empire

|

|

|

Arabic

names for the traditional Islamic months used on the religious

calendar. Also known as the

Hijra, Hidjra, Hicra, Hegira, or Hijri Calendar (in Turkish: Hicri-Kameri). This is a lunar calendar. |

Turkish

names for the traditional Islamic months used on the religious

calendar. (cf.

|

|

Muharram

(Month 1)

|

Muharrem

|

|

Safar

(Month 2)

|

Safer

|

|

Rabi

I | Rabi 1 | Rabi al-Awwal (Month 3)

|

Rebinlevvel

| Rebiulevvel

|

|

Rabi

II | Rabi 2 | Rabi al Thani (Month 4)

|

Rebinlahir

| Rebiulahir

|

|

Jomada

I | Jomada 1 | Jumada'l-Ula (Month 5)

|

Cemaziyelevvel

| Cumadelula

|

|

Jomada

II | Jomada 2 | Jumada'l-Akhira (Month 6)

|

Cemaziyelahir

| Cumadelahire

|

|

Rajab

(Month 7)

|

Recep

| Receb

|

|

Sha'ban

(Month 8)

|

Saban

|

|

Ramazan/Ramadan

(Month 9)

|

Ramazan

|

|

Shawwal/Shavval

(Month 10)

|

Sevval

|

|

Dhu'l-Qa'dah

| Dhu'l Qa'da | Zilqada (Month 11)

|

Zilkade

|

|

Dhu'l-Hijja

| Zilhajja (Month 12)

|

Zilhicce

|

The new system (fiscal) calendar months are listed in Table 1.2 and their names are written in osmanlica in Figure 1.9.

Table 1.2 Month Name in New System (NS) fiscal (solar) calendar. Denoted as sene-i-maliye or sene-i rumiye or maliya Mart Nisan Mayis Haziran Temmuz Augstos | Aghostos | Agustos Eylul | Eilul Teshrinievvel | Tishrin-i-evel | Tis,rin-i-evel Teshrinisani | Tishrin-i-sani | Tis,rin-i-sani Kanunuevvel| Kanun-i-vel | Kanun-i-evvel Kanunusani | Kanun-i-sani Shubat | Shobat | S,ubat

Figure 1.9 The Ottoman fiscal months written in Arabic script. Adapted, with permission from: Rose, Richard B: Reading Ottoman Dates: Reference Guide. OPAL (Oriental Philatelic Association of London) Publications, 1988. ISSN 0267-8071.

Lists of Ottoman Vilayet/Sanjaks for the years 1831, 1872, 1874, 1877/78, 1881/82-1893, 1894, 1895,1896, 1897, 1899,1906/07, and 1914 are contained in Karput (1985). In addition to census records, each vilayet kept an annual "yearbook" (salname) which included information about births/deaths in each province. Vilayet salnames are available for sale from the University of Chicago.

Pricing information is available at: http://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/su/mideast/Vilayet_Salname.html Good academic references for Ottoman history can be found at: http://ottoman.home.mindspring.com/

Continued on Page 2