Judeo-Spanish

by Prof. Haïm-Vidal Sephiha, Professor Emeritus, Université Paris Sorbonne Nouvelle

in Yiddish

and Judeo-Spanish, a European Heritage

published by

the European Bureau for Lesser Used Languages

with the financial

assistance of the European Commission

Origins

On 31 March 1492, the Spain of three religions (Christianity, Islam and Judaism) followed the example of other European nations. After the fall of Grenada, which marked the end of the Reconquista, the Catholic monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, decided to expel those Jews who refused to convert to Catholicism.

The nearly 200,000 Spanish Jews who went into exile in Portugal, northern Europe and the entire Mediterranean basin were called Sepharades or Sephardim, based on the Hebrew name for Spain, Sepharad (these words have at times been written alternatively with "f" rather than "ph").

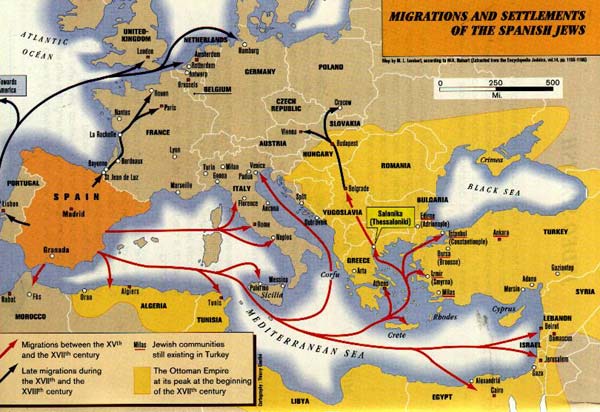

Migrations of the Spanish Jews

In general, the Spanish Jews integrated into existing Jewish communities and adopted their language after a certain time. However, in the north of Morocco and in the nascent Ottoman Empire they retained their Spanish language and imposed it on the resident Jews, and even non-Jewish communities used the language in trade relations.

However, the culture and language of the Spanish Jews was to follow a new path. As it evolved outside Spain, the archaic 15th century Castilian was soon considered to be specifically Jewish. From this came the name Judeo-Spanish, which is used in this text with its accepted linguistic meaning.

Before the Second World War and shortly thereafter, communities of Spanish Jews still banded together in northern Europe (France, England, Belgium, the Netherlands, etc.) under the name Sephardim or Sepharades, but an excessively simplistic dichotomy divided Judaism into two branches. In contrast to the Ashkenazi Jews who spoke Yiddish or Judeo-German, and confusing rites with ethnic origin, any Jew who was not an Ashkenazi came to be called a Sephardi, whether he spoke Spanish, Arabic, Iranian, Greek or any other language subsequently acquired (while, for example, Roman Catholics are not all necessarily Italian!). This was the result of recent changes such as new migrations due to the phenomenon of decolonisation. This is the case of north African Jews who use the Sephardic rites but are not of Sephardic origin. Thus, the content has changed but the label remains the same. In contrast, the Jews of Rhodes who settled in the Congo/Zaire and later in Belgium are truly of Sephardic origin.

For the purpose of this publication, the term Sephardim will be used when speaking of the Judeo-Spanish speakers. This covers all Jews from northern Morocco and from the former Ottoman Empire, including their present-day descendants who are dispersed to the four corners of the earth. These people are helping to preserve the Spanish of 1492, or at least the Judeo-Spanish vernacular which sprang from it. We also include those who adopted this language by integrating into Judeo-Spanish communities.

Therefore, it is to those Jews who so "miraculously" preserved their language and culture for more than four centuries, to their slow agony during the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire, to their fate and to their brutal death under the steamroller of the Nazi regime, that these pages are dedicated.

Judeo-Spanish, a language of fusion and a living museum for 15th century Spanish

According to the linguist B. Pottier, when the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, they took with them the varieties of Spanish - Leonese, Aragonese and especially Castilian (the language of the Court) - that were common to those who practised the country's three religions. These form the substratum of that which, around 1620, would become the Judeo-Spanish vernacular, known as Spaniol, Judezmo, Judy¢, Jidy¢ (according to Edgard Morin), Spaniolith (Spaniolish for the Nobel Prize winner Elias Canetti) or Espanioliko in the Middle East, Haketiya in northern Morocco or Tetuani in the region around Oran in Algeria. All of these terms designate the Judeo-Spanish vernacular, which would in turn also evolve. We say around 1620, because the process by which travellers from Spain stopped being able to understand the ancestor of their language in the Spanish spoken by the descendants of those they had expelled was a gradual one and attributed Jewishness to these people. Similarly, the Muslim Turks who knew Spanish only via the Jewish minority called the language Yahudije (Yahudice means "Jewish" in Turkish). Thus, by means of a historical mistranslation, the Spanish Jews' language became their identifier. Judy¢ (Jew) designates both the language (the Judeo-Spanish vernacular) and the speaker of Judeo-Spanish (the Sepharad), as is the case with Yiddish (Ger., J?disch meaning Jew) for the Ashkenazim. By means of a similar mistranslation, we would have probably attributed a Judeo-French language to the French Canadians if they had been Jews! This is absurd, and yet the name Judeo-Spanish has stuck.

Judeo-Spanish, a language of fusion, is essentially 15th century Castilian, coloured initially by regionalisms and hispanic Arabicisms, and after 1492 by Moroccan Arabicisms, Turkisms, Italianisms, Hellenisms, Slavisms, etc. taken on in the various host countries. Later, with the creation of the schools of the Alliance Israelite Universelle in 1860, the language was affected by a mania for gallicization, to the point that a new dialect called judeo-fragnol (Judeo-Franco-Spanish) emerged.

We said in our subtitle that Judeo-Spanish is a living museum for 15th century Spanish. Indeed, in 1492 - the date of the Jews' expulsion from Spain - Castilian had not yet undergone the silencing of voiced sibilants or the birth of the jota. Thus, the intervocalic [z] of that time remains, and one continued to say [meza] for mesa, (with [s], "table"). Similarly, one continued to say [ka's'a] for caja, "box" or "crate," or [pa'z'a] for paja, or "straw." It is precisely for this reason that Don Quixote [Don Ki's'o-te], which is now written Don Quijote - with jota - arrived in France as Don Quichotte, with [ch], reflecting the pronunciation of that time.

The distinction between [b] and [v] would also be maintained: [kantava] for cantaba, "I" or "he sang." Other archaic forms also persisted: kavdal - kovdisya - kovdo - sivda etc., which later became caudal in Spanish, "goods or fortune," codicia"cupidity or covetousness," codo "elbow," ciudad "city," etc.

There are also numerous "vulgarisms" from that time: agora - prove - guevo - guerfano, etc. for ahora, "now," - pobre "poor" - huevo "egg" - huerfano "orphan." Similarly, the two forms muevo/nuevo coexist for "new.".

Morphology: The old verbal forms do- vo- so and esto for doy "I give" voy "I go," soy "I am" and estoy both "I am" in English, continued to be used. As in the popular Spanish language, the second person forms of the simple past already had a tendency to take on a final -s. The metathesis >ld of the imperative form also continued to be used: kantadlo>kantaldo "sing it."

These observations obviously provide only a few examples illustrating a much broader topic.

In its subsequent evolution, Judeo-Spanish would develop particularly interesting strategies for hispanizing various loan words. Thus, there is continued use of the frequentative verbal ending -ear, as a verbal hispanizer for all loan words from the Turkish, Arab, Bulgarian, Greek, etc. host countries (adstrates), except for those of French origin, which take the -ar ending. Thus, from the Turkish dayanmak, "resist, endure," we get the Judeo-Spanish form dayanear. In contrast, based on the French "s'amuser" (to enjoy oneself), we have the form amuzarse. On the other hand, the ending -dero, which is very frequent in Spanish, is maintained but is used especially in forming words for obsessions or habits. We see this, for example, in the word arraskadero, whose meaning shifted from "pruritus, itching" to "obsession with scratching."

Vocabulary and semantics (Spanish archaic usages): there are many examples: merkar (to buy), trokar (to change), mansevez (youth), etc. The feminine gender of some nouns ending in -oris also kept, while these have become masculine in standard Spanish.

But along with these archaic usages, which are very understandable given the historical path of the language, there are also some genuine lexical creations based on Ladino (Judeo- Spanish calque), produced by the word-for-word translation from Hebrew into Spanish, which go back to the 13th or even the 12th centuries. All of these terms that are more archaic than the vernacular language are, via the intermediary of Ladino, a faithful reflection of the sacred languages (Hebrew and Aramaic), which makes them semi-sacred. By way of example, akunyadar/ear, which means "to fulfil the Levitical law," (i.e. the obligation found in the law of Moses for the brother of a dead man to marry the dead man's childless widow).

So, we can see that Judeo-Spanish is a language of fusion. Four percent of its loan words come from Hebrew, 15 percent from Turkish, 20 percent from French, two percent from Ladino, etc., with all of these built on the foundation of the 15th century Spanish substratum.

Problems of Judeo-Spanish

Ladino is not spoken, rather, it is the product of a word-for- word translation of Hebrew or Aramaic biblical or liturgical texts made by rabbis in the Jewish schools of Spain. In these, translations, a specific Hebrew or Aramaic word always corresponded to the same Spanish word, as long as no exegetical considerations prevented this. In short, Ladino is only Hebrew clothed in Spanish, or Spanish with Hebrew syntax. The famous Ladino translation of the Bible, the Biblia de Ferrara (1553), provided inspiration for the translation of numerous Spanish Christian Bibles.

Apart from the phonetic, morphological and syntactic differences mentioned above (which are very rare, especially in the romances and proverbs), the spoken language, Judezmo (the Judeo-Spanish vernacular) does not differ much from peninsular Spanish. However, as mentioned above, Ladino faithfully reflects the sacred languages (Hebrew and Aramaic), making it semi-sacred.

Spelling

In Spain, two alphabets were used, the Latin and the Hebrew. The Ladino of the Ferrara Bible was written in Gothic-style Latin characters for the Marranos of Spain, who returned to Judaism but knew no Hebrew. Around 1928 in Turkey, at the behest of the new republican power of Mustapha Kemal Pasha, Latin script replaced the Hebrew script. However, for quite some time the elders used Solitreo, Hebrew manuscript writing, which even served as a secret form of writing in the Nazi concentration camps.

Today, Sephardim write their language according to the alphabet used in their country. In this text, we use the French- influenced spelling of the Paris-based Association Vidas Largas for the Defence and Promotion of the Judeo-Spanish Language and Culture.

Old Judeo-Spanish literature (through 1850)

There are essentially two types: liturgical and secular.

The old liturgical literature (Bibles, prayer books etc.) was written in Ladino, both in the East and the West (Morocco, Bordeaux, Amsterdam, etc.). It was not until 1730 that texts were written in Judezmo, notably the famous "Me'Am Lo'ez," a popular 18-volume encyclopedia published between 1730 and 1908. Secular literature was passed on mainly in oral form: proverbs, romances, "kantigas," tales and fables - all forms which began by perpetuating the Hispanic heritage and then took inspiration from daily life in the Ottoman Empire and northern Morocco.

The numerous proverbs are an inexhaustible source of linguistic and cultural interest; thus, it is not surprising that they are the subject of studies and investigation, notably at the Arias Montano Institute in Madrid.

The Sephardic "romancero" - which celebrates more or less recent events, like the execution in Fez in 1820 of Sol Hachuel, a young Jewish woman who refused to convert, or the "Gran fuego," a terrible fire that devastated Salonika in 1917 - has been particularly long-lived.

This oral literature is of considerable importance for Spain as well, because through it one has access to aspects of the country which seemed to have been lost forever. The Jews, faithful to their ungrateful homeland, have conserved this Spanish of old in their living museum.

Modern literature (1850 to the present)

There has been a progressive westernization of the Sephardic communities under the combined influence of the schools created by the Alliance Isra,lite Universelle (52 schools in European Turkey alone) and the press (more than 300 newspaper and magazine titles). This has resulted in a new intelligentsia that is westernized, gallicized and secularized to some extent and has ushered in new literary genres such as theatre and secular poetry, novels and numerous translations/adaptations of European works.

The French language became increasingly invasive (notably through teaching), resulting in a new form of the language in the Ottoman Empire - Judeo-Franco-Spanish, as mentioned above.According to Michael Molho, starting in Istanbul in 1832, the two modes of Judeo-Spanish (Ladino and the vernacular language) have given rise to a significant body of literature: 5,000 to 6,000 works, not including the 300 press titles which then flourished. Hundreds of plays have also been discovered since that time.

The fate of the Judeo-Spanish - Dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire

The slow dismembering of the Ottoman Empire began in 1699, with the breaking off of Hungary and Transylvania, and ended with the proclamation of the Turkish Republic by Ataturk in 1923. This systematic erosion was aided and abetted by a host of minor interests, including viziers, pashas and partisans of various strains of nascent nationalism, as well as the major powers - Austria-Hungary, Russia, France, England - as they knotted and unknotted their alliances, and recently unified nations like Germany and Italy. The Turkish minorities, or millets - Greeks, Armenians, Jews, etc. - within this veritable republic of nations, were courted by the West. Each State created its own schools. This contributed to the Judeo-Spanish emigrating from both the Levant and in Morocco to Europe and the Americas starting in the end of the 19th century. Wave followed wave until 1939, and longer for Morocco.

Lost unity

Within the Ottoman bloc there was a united Judeo-Spanish bloc, for which the cities of Salonika, Kavalla, Adrianople, Constantinople, Smyrna, Sofia, Sarajevo, Jerusalem, Safed, Alexandria and Cairo served as guiding lights. Rabbis and advisors were sought there by the entire Sephardic world: Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Antwerp, Brussels, Paris, Corfu, London, Venice, Milan, Livorno, Hamburg, Altona, Buenos Aires, Mexico City, New York, Miami, Santiago de Chile, etc.

The dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire brought the disintegration of this bloc. Spanish Judaism had lost its glue. Sephardim again went into exile. In their new host countries, they were faithful to their language and established religious and ethnic communities.

One international magazine, Le Judaïsme Séphardi, served as their link. However, in 1948, in the United States, the last Judeo- Spanish newspaper printed in Hebrew characters, La Vara, stopped being published.

The Holocaust, 1939-1940 - A language assassinated

World War II and the Holocaust with its genocide would soon decimate the Judeo-Spanish population:

- In Greece, there were 79,950 in 1940 but only 10,371 in 1947. Thus, more than 50,000 Sephardim perished there.

- In Yugoslavia, there were 71,000 in 1940 but only 14,000 survivors in 1944, of which 8,000 were authorised to emigrate to Israel. 55,000 Sephardim perished in Yugoslavia.

- In Romania, at least 15,000 Sephardim perished.

- In Bulgaria, there were 40,000 in 1940 and 50,000 in 1947. No Jews were deported from Bulgaria thanks to the Bulgarian people's fierce opposition to the extermination of their Jewish compatriots. In 1949, only 9,700 were left, the others having emigrated to Israel, where their melodious language can still be heard today in the streets of Tel Aviv and Bat Yam in particular.

- In addition to these victims, there are the Sephardim who emigrated within Europe, where the Nazi occupation took them by surprise. 60,000 perished. In all, around 160,000 Sephardim perished out of the 365,000 counted in 1925. The Sephardim of Morocco were protected, but left the country en masse during the decolonisation process.

The Sephardim today

Their numbers are, of necessity, approximate, 378,000 in all, broken down as follows: Israel - 300,000; Bulgaria - 3,000; Turkey - 15,000; northern Morocco - 3,000; New York and the US in general - 15,000; Greece - 2,000; France, Belgium and England - 40,000.

This trend continues, because although the number of those who acknowledge Judeo-hispanicity is probably much higher (we are thinking here of Jews in Latin American countries, where the number of those who still speak their language of origin is dropping quickly). Moreover, all or nearly all are bi- or tri- lingual. In Israel, the last major reservoir of Sephardim, the understandable hebraization is also undermining the presence of Judeo-Spanish. The only magazine still written entirely in this language, Aki Yerushalayim, is a sort of symbol for all of the nostalgia concerning Judeo-Spanish throughout the world. In the Turkish weekly alom, only one page in between six and ten is in Judeo-Spanish. These are the two survivors of a once- thriving press that boasted over 300 titles.

A renaissance for Judeo-Spanish through its literature

For more than 30 years, Judeo-Spanish literature, both prose and poetry, has been blossoming. Examples are "En torno de la Torre blanca," a moving chronicle set in Salonika by the novelist Enrique Saporta y Beja, and "El sekreto del mundo" by Itzak Ben- Rubi, which brings the world of the concentration camp to life. Poets include Clarisse Nicoidski, who writes novels in French and poems in the language closest to her heart, Balkan Judeo-Spanish, Salamon Bidjerano and his "Kantes de Maturidad," and Lina Albukrek, the author of delicious poems that were faithfully compiled by her daughter in a book entitled "87 anios lo ke tengo."

We should add to this all-too-brief list all of those who compiled tales, proverbs and romances, thus helping to safeguard this precious heritage. They include Israeli Matilda Koen- Safrano's compilation entitled "Kuentos del folklor de la Famiya Djudeo-espanyola" and Jaime B. Rosa's book entitled "Sepharad 92," which contains a collection of poems by Avner Perez, Izan Konorti, Isahar Avzaradel, etc.

Finally, there are works in other languages which keep the memory of Judeo-Spanish alive. Some of these include Annie Benveniste's chronicle "Le Bosphore a la Roquette," Brigitte Peskine's "Les eaux douces d'Europe" and Nelly Kafsky's "Le rêve d'Esther," which was adapted very successfully for television.

Judeo-Spanish in universities

Today, attempts are being made to recover the remains of this culture. Universities have become involved in this, and the number of teaching posts for Judeo-Spanish (language, culture and civilization) are increasing throughout the world. The first was created in Paris - at the Ecole des Langues et Civilisations Orientales Vivantes - in 1967, and the Sorbonne (Institut d'Etudes Hispaniques) and the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes followed suit. The Université Libre de Bruxelles (Institut Martin Buber) did the same in 1972. In these establishments, where H.V. Sephiha teaches, more than 400 master's and doctoral theses have been written on this discipline, which the author calls Judeo-hispanology.

Judeo-Spanish is also studied in conjunction with the study of dialects in all linguistic courses in Hispanic or Iberian faculties in French universities.

The same goes for universities in Spain, where the Arias Montano Institute in Madrid has published the magazine Sefarad since 1941, which is to Judeo-Spanish what the magazine Al-Andalus is to Spanish Islam.

In Germany and other European countries, Judeo-Spanish is taught in the Romance language department of universities. One example is the Institut fur romanische Philologie of the Freie Universitat of Berlin. Judeo-Spanish is also a topic of interest at the universities of Tubingen, Munich, Trier, Aachen, and Frankfurt, and in Innsbruck in Austria, in Fribourg, Neuchftel and Geneva in Switzerland, and in the Spanish language departments of the universities of Venice and Padua. Other universities also touch on the subject in their departments of Iberian or Hebrew studies. Hispanic studies departments in England are interested in Judeo-Spanish as well.

Numerous university correspondents in the above mentioned countries as well as Greece, Poland, former Czechoslovakia, Hungary, the former USSR, Bulgaria, Romania, former Yugoslavia, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden and Norway have announced the creation of teaching and research centres for this discipline. This shows the importance that is attributed to it.

In Israel, after a certain rejection of the languages of the Diaspora, awareness began to grow regarding the linguistic and cultural wealth of Judeo-Spanish. At present, this discipline is taught in most Israeli universities.

In addition to the Judeo-Spanish language, the literature and, in particular, the Judeo-Spanish romancero are drawing the attention of specialists in Spanish literature in universities in France and abroad. An example of this is the recent bilingual anthology of Spanish poetry by La Pleiade and the production of many records of Judeo-Spanish songs over the last three decades.

Community education and life

Community education is also important. In France, the Vidas Largas Association for the Defence and Promotion of the Judeo- Spanish Language and Culture was created in 1979, making it possible to bring Judeo-Spanish instruction into the Communities of Paris, Marseille and Lyon. Similar things are happening in the context of the association Los Muestros (http://www.sefarad.org/) in Belgium and throughout the world.

There has also been a great revival of interest in Judeo-Spanish culture. Examples are the many magazines and bulletins being published throughout the world. There is also evidence of this cultural renaissance on the radio, with daily broadcasts in Israel and Madrid, a bi-weekly programme in France and a weekly programme in Belgium.

The future of Judeo-Spanish

All of the above is very encouraging. Death throes have given way to rebirth. However today, while parents attend to their lucrative occupations, it is often the grandparents who introduce the children to Judeo-Spanish and instill in them an interest in their past.

The message is getting across, and this trend appears to be irreversible, but we must continue to consolidate and protect the heritage of the ancients. It is to this end that Judeo-Spanish workshops are being created everywhere, in collaboration with a growing number of researchers.

Associations, magazines, and periodicals

- Vidas Largas, Association and Magazine for the Defence and Promotion of the Judeo-Spanish Language and Culture: 37, rue Esquirol, 75013 Paris. This association has three branches: in Marseille, Lyon and Geneva.

- France Mabatt, Association of Sephardim from northern Morocco: c/o J. Pimienta, 128, rue Legendre, 75017 Paris.

- Nouvelles de l'Institut d'Etudes du Judaïsme, ULB, Brussels.

- Los Muestros, La boz de los Sefardim - La voix des Sépharades - The Sephardic Voice: Rue Hotel des Monnaies, 52 B-1060 Brussels http://www.sefarad.org

- Sefarad, Arias Montano Institute: CSIC Medinaceli, 4, Madrid 14.

- Annual (Godichnik): Social and cultural organisation of Bulgarian Jews: 50 boulevard Stamboliisky, Sofia.

- Erencia (United States). Dr Albert de Vidas, 46, Benson Place, Fairfield, CT 06430, USA.

- Aki Yerushalayim, Jerusalem - in Judeo-Spanish only - P.O. Box 1082 Jerusalem.

- Shalom, Istanbul, weekly in Turkish, 1/6 in Judeo-Spanish.

- Jevrejski Pregled, Federation of Jewish Communities of Yugoslavia: Ul. 7 jula, 71a post, fah 881, Belgrade.

- Israelite Community of Thessaloniki: 24, Tsimiski St., Thessaloniki.

- World Sephardi Federation: 67/8 Hatton Garden, London.

Concise Bibliography

- BUSSE, W., Hommage to Haïm Vidal Sephiha, in Sephardica, Peter Lang, Exhaustive bibliography of H.V. Sephiha, pp. 21-63. 1996.

- DIAZ-MAS, P., Los Sefardies, Historia, lengua y cultura. Riopiedras Ediciones. 1986.

- KOEN-SARANO, M., Kuentos del folklor de la famiya djudeo-espanyola, in Judeo-Spanish and Hebrew. Ed. Kana, Jérusalem 1986.

- HASSAN, J.M. & ROMERO, E. (ed), Actas del Primer Simposio de Estudios Sefardies. C.S.I.C., Madrid 1970.

- LEROY, B., L'Aventure séfarade, de la péninsule ibérique a la diaspora. Albin Michel, Paris 1986.

- RENARD, R., Sepharad. Annales de l'Université de Mons, Mons 1966.

- SACHAR, H.M., Adios Espana, Historia de los Sefardies. Thassalia 1995.

- SEPHIHA, H.V., L'agonie des Judéo-Espagnols. Ed. Entente, "Minorités" collection, Paris 1977, 1979 et 1991. (With a chapter on the Judeo-Spanish press).

- SEPHIHA, H.V., Le judéo-espagnol. Ed. Entente, "Langues en péril" collection, Paris 1986.

- SEPHIHA, H.V., Contes

judéo-espagnols - Du miel au fiel. Translated and presented by H.V.

Sephiha. Ed. Bibliophane, Paris 1992.

Note: Prof. Haïm-Vidal Sephiha is also president of J.E.A.A (Judéo-Espagnol A Auschwitz). The organization launched in 2000 an international campaign to obtain an additional plaque in Judeo-Spanish at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial in remembrance of the Jewish Martyrs who had Judeo-Spanish as their mother language. http://www.sepharadshoah.org