Sephardic Jewish Community of Romania

Introduction

Extending inland halfway across the Balkan Peninsula and covering a large eliptical area of 237,499 square kilometers (91,699 sq. mi.), Romania occupies the greater part of the lower basin of the Danube River system and the hilly eastern regions of the middle Danube basin. It lies on either side of the mountain systems -- the Carpathians and the Transylvanian Alps -- that form, with the Balkan Mountains, the natural barrier between the two Danube basins.

About 89% of the people are ethnic Romanians, a group that--in contrast to its Slav or Hungarian neighbors--traces itself to Latin-speaking Romans who in the second and third centuries CE conquered and settled among the ancient Dacians, a Thracian people. As a result, the Romanian language, although containing elements of Slavic, Turkish, and other languages, is a Romance language related to French and Italian.

The dwindling Jewish community in Romania numbers about 14,000 out of a total population of 23.5 million. This population is mostly Ashkenazic Jews, but at one time many Sephardim lived with in Romania's borders. Today the major centers are in Bucharest, Iasi, Cluj and Oradea. Jewish life is also fostered in some smaller communities, and relics of the past are preserved in locations where there are no longer any Jews. The Federation of Jewish Communities is the main coordinating body for Jewish activities, and its publications and symposia are well covered by the Romanian media. It publishes a monthly, Realitatea Evreiasca.

Early History as Part of the Ottoman Empire

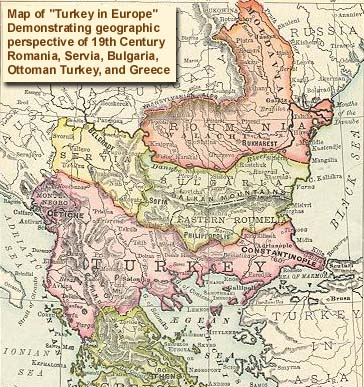

From the Middle Ages to the modern times the Romanians lived in three distinct but neighbouring principalities: Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania. Located in an area of intersection of the borders of several powerful kingdoms and empires, their territory became an area of dispute and, at the same time, of cultural confluence. In the second half of the 14th century a new threat against the independent Romanian lands emerged: the Ottoman Empire. After first setting foot on European soil in 1354, the Ottoman Turks began their rapid expansion on the continent.

The whole Balkan Peninsula became a Turkish-ruled territory, Constantinople was captured by Mohammed II (1453), Suleiman the Magnificent captured the city of Belgrade (1521), and the Hungarian kingdom disappeared following the battle of Mohacs (1526). Therefore, Wallachia and Moldavia were surrounded and they had to recognize for over three centuries the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire.

The end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century brought about changes in the politics of Central and Eastern Europe. The Ottoman Empire failed to capture Vienna in 1683 and following that, the Hapsburg Empire began its expansion to the southeast of Europe. The Austrian-Turkish peace treaty of Karlowitz (1699) sanctioned the annexation of Transylvania and its organization as an autonomous principality to Hapsburg Austria (since 1765 great principality), ruled by a governor. The Ottoman Empire, in an attempt to defend its old position, introduced in Moldavia (1711) and Wallachia (1716) the "Phanariot regime," (until 1821), under which the Sublime Porte appointed in the two principalities Greek voivodes recruited from the Phanar district of Istanbul and considered faithful to the Turks. That was a time when the Ottoman political control and economic exploitation increased and corruption spread;

Many wars were fought by Austria and Russia against the Ottoman Empire (1710-1711, 1716-1718, 1735-1739, 1768-1774, 1787-1792, 1806-1812, 1828-1829, 1853-1856): those battles took place on Romanian soil, always accompanied by a foreign military occupation, which was often maintained long after the war proper was over. Thus the Romanian lands endured not only through devastation and irrecoverable losses, but also through population displacements and painful territory amputations.

Romania proclaimed its independence from the Ottoman Empire on May 9, 1877, and participated alongside Russia in the war against the Turks. In 1881 Romania became a kingdom, an event that marked of the country both domestically and internationally. The continual threat posed by Russia determined the leadership of the country to enter into an alliance with the Central Powers in 1883. With the achievement of national independence, Romanians in neighboring territories still under foreign domination began to look to Bucharest for inspiration.

Modern History

The peace treaty of 1829 signed at Adrianople (today Edirne) ended the Russian-Turkish conflict of 1828-1829, which had broken out in the final stage of the war for national liberation fought by the Greeks; this treaty greatly weakened the Ottoman suzerainty.

Figure 1. Map of Ottoman Turkey in Europe (Circa 1885)

In the first half of the 19th century, the Romanian principalities began to distance themselves from the Islamic Ottoman world and tune into the spiritual space of Western Europe. Ideas, currents, attitudes from the West were more than welcome in the Romanian world, which was undergoing an irreversible process of modernization. An awareness that all Romanians belong to the same nation was generalized, and the union into one single independent state became the ideal of many Romanians. The modern Romanian nation was founded in the winter of 1862; its capital was chosen to be Bucharest.

Sephardic Romania

Documents demonstrate Spanish Jews in Wallachia as early as 1496. These most likely stemming as a result of the Iberian diaspora, and the acceptance into (Ottoman) Romania and other Bakan states by Sultan Beyazid II.

In 1718 the first Hahambasi (Betalel Cohen) the son of Rabbi Naftali Cohen, Sultan Mustafa III's protege, was appointed by Romanian Prince Alexandre Ipsilanti. These Hahambasi would be in charge of all the Jews in the entire country. His office was in Jassy, but he still had juristdiction of Jews in the southern territories of Wallachia. This cheif Rabbi had officers spread through out the Romanian state called vekil Hahambasi, which were located in major cities. The office of the Hahambasi lasted until 1834 when it dissolved. Instead of the Prince making a Rabbi the Hahambasi, it was now up to the Jewish people to elect their own spiritual leader. In losing the title of Hahambasi, future spiritual leaders also lost the rights (and protections) that came along with it.

Most of the original Jewish population of Romania arrived from Turkey and the Balkans and was made up of Sephardim. However, by the nineteenth century, the majority of the Jewish population of Romania was made up of Ashkenazim, the result of waves of Yiddish speaking immigrants from Galicia and Russia.

Transylvania was on a trade route between the orient and the west, and northern and southern Europe. Because of this, the first Jews arrived on these trade routes to Transylvania from Turkey and the Balkans. The first Jewish community was in Alba Julia, which has records of Jewish residency as early as 1591. At one time an independent state, Transylvania was later incorporated as part of Hungary, and then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Jews continued to migrate to Transylvania in small numbers throughout the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, even though there were residency restrictions until 1848.

The number of Jews in historic Transylvania jumped from two thousand in 1766, to thirty thousand in 1880. Timosoara, a city bordering the Balkan states in the Banat region of Transylvania, was first settled by Turkish Sephardim, prior to German culture becoming dominant in later centuries. In 1762, both Sephardi and Ashkenazi synagogues were built in Transylvania, with many Sephardic Jews known to be living in various towns such as Dej, Carei and Cluj. For many years small Sephardic communities of Ladino speakers functioned in the port towns of the Danube and in Southern Dobrudja.

Figure 3. Map of Romania as it was in 1897 CE with locations significant to Sephardic Jewish populations.

Click image to Enlarge

Romania's Jewish population entered the principalities in the 1800s, moving south out of the Russian Empire: for that reason the northern province of Moldavia became center of Jewish life. In 1803 there were only 15,000 Jews in Moldavia, but by 1859 there were 118,000; and in 1899 there were 197,000. Fewer Jews lived in Wallachia: 4,000 in 1831; in 1859 the figure was 9,000; and in 1899, the total reached 61,000. Another 75,000 Romanian Jews emigrated in the period 1881-1914, mostly to the United States.

Family Surname Variants

Many Jews of Romania absorbed the naming practices of their community; this is not unlike elsewhere throughout history. Many of the Jews took the typical Romanian suffixes of -escu, -eanu and -aru and Romanianized their original traditional surnames.

Avramescu, Isacescu, Iocabescu Aroneanu, Ocneanu, Podoleanu, Focsaneanu (from the town of Focsani) Ciubotaru (bootmaker), Fainaro (miller), Sticlaru (glazier) The various Sephardic-specific surnames of Romania demonstrated the multi-ethnic roots of the Sephardim. This includes the names: Aftakion, Alcaly, Alfanderi, Behar, Graniani, Medina, Mitani, Nahmias, Papo, and Semo. These representing Spain, Italy, Greece, Turkey, and the Arabic countries.

The Holocaust and Beyond

In the summer of 1940 Romania succumbed to German pressure and transferred Bessarabia and part of Bukovina to the Soviet Union, northern Transylvania to Hungary, and southern Dobrudja to Bulgaria (the territory that remained being called Old Romania). Anti-Semitism flared, and in 1941 many pogroms occured. Jewish homes were looted, shops burned, and many synagogues desecrated, including two that were razed to the ground (the Great Sephardi Synagogue [Kahal Grande] and the old bet ha-midrash). Some of the leaders of the Bucharest community were imprisoned in the community council building, and worshipers were ejected from synagogues by force.

Over 264,000 Jews perished in Nazi death camps during World War II. Most of the survivors fled postwar communism and emigrated to Israel or the United States. Only 14,000 Jews, most aged over 60, live in Romania today.

Click here to see a list if Rabbis of the Capital of Romania (Bucharest)

References

- Calafeteanu, Ion. The History of the Romanians: Embassy of Romania, Oslo, Norway 1997.

- Ofer, Dalia. Struma. Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. Ed. Israel Gutman. New York: Macmillan Library Reference USA, 1990.

- Halevy, Mayer A. Contributiuni la istoria Evreilor in Romania: Bucuresti, 1933.

- Iancu, Carol. Jews in Romania. Columbia University Press: 1996.

- Jerusalem, Summer 1998 The Hebrew University The Faculty of Humanities : Newsletter 14.

- Stoian, Mihai. Ultima cursa de la Struma la Mefkure Bucuresti: Editura Hasefer, 1995.

- Wasserstein, Bernard. Britain and the Jews of Europe, 1939-1945. London: Clarendon Press, 1979.

- Yahil, Leni. The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.