Ottoman Sephardic Genealogy: An Introduction

Page 3.

by Dr. David Sheby Continued...

1.3.3 Example 2: Pronunciation of a family name

One branch of an Ottoman Sephardic family emigrated to the U.S. and spelled the family beginning with "SH. A second branch emigrated to South America, and began their name with "CH", pronouncing "CH" as in Spanish (not the "CH" of French). A question rose over which branch correctly preserved the family's traditional pronunciation. Documentation from modern Turkey (i.e., post 1928 tombstones and correspondence) showed the family name spelled using the "s-cedilla" letter (see Figure 1.14) thus supporting the "SH" pronunciation

1.4 Introduction to Ottoman Geography: the "Vilayet" (Province) on the Birth Certificate

In this section the place names of the Ottoman Empire are introduced. Additional detail is covered in Section 4.0 (Ottoman Place Names).

The Ottoman Empire kept meticulous records. The Ottomans were great tax collectors, and for tax collection to be efficient, an accurate assessment of expected revenue had to be regularly determined (i.e., the identities, assets, and tax liabilities of potential taxpayers). As a result, the Ottomans took regular census surveys of their territories. There were also geopolitical motivations for census-taking. The Ottoman Empire needed to know the ethnic composition of its various territories (particularly in the Balkans where there was a significant non-Moslem population), especially where there were vulnerabilities to external groups seeking to assume the role of protector for segments of the Empire's citizenry. Census records could identify vulnerabilities, and dispute claims concerning majority/minority ethnic compositions. As a result the study of Ottoman census/demographic records is of prime importance to academics studying Ottoman history. The classic work detailing Ottoman censuses and their results is:

Karpat, Kemal H.: Ottoman Population 1830-1914, University of Wisconsin Press, 1985 ISBN 0-299-09160-0

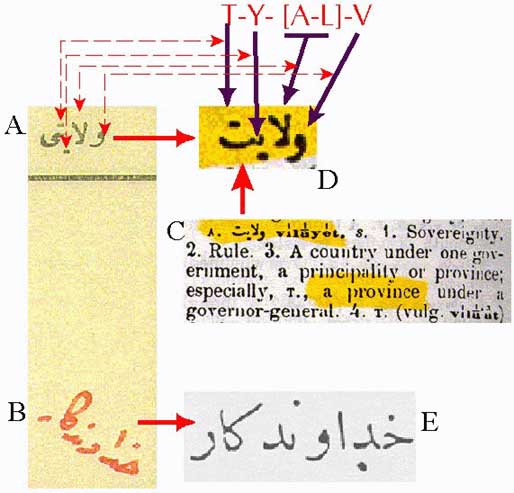

For such administrative purposes, the Ottoman Empire was composed of administrative units, the largest unit being a "province" known as the vilayet (alternative name: "eyalet"). The vilayet is recorded on the Ottoman birth certificate (see Figure 1.1: box translated as "state", isolated as Fig. 1.9 [1]). The Ottoman birth certificate's spelling for vilayet (Fig 1.9 [1a] enlarged as Fig. 1.9 [2c]) is defined as "province" (ruled by a Governor) in the standard Ottoman-to-English dictionary (Fig. 1.9 [2]):

A Turkish and English Lexicon: Shewing in English the Significations of the Turkish Terms (published in 1890 by Sir James W. Redhouse) (known as the "Redhouse Dictionary"). The Redhouse dictionary is available as a reprint through Librairie du Liban (Beirut: URL: http://librairie_du_liban.com.lb ISBN 975-454-000-4; Library of Congress Classification PL191.R52).

Figure 1.15

The Redhouse dictionary's spelling of vilayet (page 2,148; enlarged (Fig 1.15 [d]) matches the birth certificate's spelling (Fig. 1.15 [a]) letter-by-letter (read right to left). The vilayet handwritten entry (Fig. 1.15 [b]) is for Hudavendigar (graciously identified as such by the owner!): this is confirmed by a letter-by-letter comparison of the handwritten entry with the spelling of Hudavendigar (Fig. 1.15 [e]) contained in volume 1 (page 226) of the 5-volume set: Bayindir, Mustafa Hilma: Osmanli-Turka Posta Muhur ve Damgalari (Ottoman-Turkish Seals and Postmarks) 1840-1929. Istanbul, 1992. See: http://www.kilim.com.tr/filateli (Note: See map (Figure 7 at: http://www.sephardicstudies.org/gallipoli2.html) for location of the Vilayet of Hudavendigar.)

The number of vilayets (Table 1.5) varied with time and depended on both (1) geo-politics, and (2) administrative reorganization incentives. As the Ottoman Empire lost certain territories (e.g., Bosnia and Bulgaria in their entirety, and western Thrace to Greece and many Aegean islands to Italy) there would be the defacto loss of the vilayets within those territories. Reorganization programs would result in newly organized vilayets or resized vilayets. The names of the vilayets could also change.

Table 1.5 : Numbers of Vilayets in the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century Vilayets were divided in sanjaks (or sancak) (sub-provinces) which, in turn, were divided into kazas (cities, Fig. 1.16). Affiliated with each kaza were numerous small villages. In 1850 there were 36 eyalets comprised of 440 sanjaks, in 1890 there were 36 vilayets comprised of 146 sanjaks. The chief town of a sanjak was called the "merkez kazasi" (central kasa") The vilayet Hudavendigar contains the city of Brussa (Bursa) on Turkey's main Anatolian component. Table 1.6 lists sources of maps for Ottoman vilayets.

Figure. 1.16 Visual demonstration of a vilayet made up with sanjaks and kazas.

Table 1.6 Sources of Ottoman Vilayet Maps Year Source Map of Ottoman Vilayets 1893 Karput (2 pages) Map of Ottoman Vilayets 1890 Peker (back insert) Map of Individual Vilayets Bayindir (maps spread over 5 volumes) The Ottoman Empire's Administrative structure (vilayets, sanjaks, kazas) in 1890 can be found in: Peker, Ugur A.: Osmanli Imparatorlugu Idari Taksimat ve Posta S,ubeleri Hircri 1306, Miladi 1890 (The Administrative Division and the Post Offices in the Ottoman Empire), Berkmen Philatelics, 1984.

Return to Page 1